Museums have historically acted to tether artworks and artifacts to territorial conceptions of place. Meanwhile, as conduits to the flow of artworks across borders according to the imperatives of a globalized market, international contemporary art fairs might seem to obey an opposite logic, operating as deterritorializing forces that uproot works of art from their native geographies. Yet assigning museums and art fairs neatly to different sides of a binary that pits rootedness against a world of unhomed objects and convergent cultures obscures a more complex and dynamic reality. If large brick and mortar institutions are restructuring to satisfy new economic imperatives and economies of attention within a global regime of art circulation, exhibition, and consumption, as they proliferate to new locales with less-developed markets, many art fairs are becoming more substantially place-minded. In addition to shaping themselves according the context and needs of their host locations, global art fairs are finding new ways to address the geographical contexts and local aesthetic histories of works of art. As museums of modern and contemporary art dispense with fixed galleries and large, unmoving museum collections in favor of blockbuster installations and flexible holdings that can accommodate the demand for more globally attuned programming, art fairs have begun to assume some of the cultural functions conventionally belonging to museums.[i]

The art world infrastructure of the United Arab Emirates is perhaps a hyperbolic instance of the conflation of the market and older institutional modalities. This is because rapid oil-driven development and urbanization has meant the emergence of modern and contemporary art museums only subsequent to the development of both locally-serving galleries and an aggressive, internationally oriented art market. As the leading art fair in the region, Art Dubai has helped shape the landscape of Middle Eastern contemporary art since its inception in 2007. More than just a marketplace, however, the fair has cultivated its civic face, functioning—like many of the biggest contemporary art fairs—as a high quality temporary exhibition that attracts large non-collector audiences, and incorporating long rosters of non-commercial programs including lecture series, performances, commissions, and non-profit components. In dealing in art from “emerging” regions where postcolonial legacies and/or rapid urbanization have made histories of both modernism and modernity matters of active negotiation and dispute—histories hitherto largely ignored by the cannons of modernist art history forged in western institutions—Art Dubai has engaged with local aesthetic history in both its commercial and more public programming.

Yet, while these civic, discursive, and historicizing functions may harken to the traditional roles of the public museum, the expedient logic of the art fair’s programming is not difficult to decipher; state-funded community outreach, academically inclined discursive programming, and non-commercial exhibitions all serve to create different forms of legitimacy for the fair and the artworks therein. In a globalized art world in which an understanding of local context and art history is essential for participation in new markets, the production and dissemination of this information is an integral market tool. This expedient logic is not dissociable from the art fair’s dynamic architecture. Not unlike the globalized economy that thrives on geographic difference—discrepancies in the cost of labor power and goods, differently valued currencies, disparate laws, skewed urban development—Art Dubai functions as a spatialized array of different microlandscapes, each determined by a different relationship to the market. This variegated topography ranges from the adamantly public, such as the programs for school children run during the week, to the exclusively private, such as collectors’ previews or VIP lecture series. Each of these ephemeral zones strikes a different relationship to art, here accentuating art’s pedagogical value, there its commodity value. Yet these differences belie strategic relationships between the commercial and the non-commercial, the academy and the market, the “emerging” and the emerged. In what follows I explore how these entanglements relate to the realm of knowledge-production by looking at two features of Art Dubai 2014, Modern 2014, the inaugural instantiation of the fair’s section devoted to modern art from the Middle East and South Asia, and Marker, a not-for-profit program devoted to a different emerging region each year. I argue that the effects of the market’s role in helping consolidate histories of modernism in these regions are deleterious, and I identify a neo-imperialist logic in the discourse surrounding emerging markets. Lastly, I briefly examine Art Dubai’s relationship to the yet-to-open Guggenheim Abu Dhabi to show how the fair’s role in tethering artwork to conceptions of place coincides with the logic of deterritorialization at play in the museum.

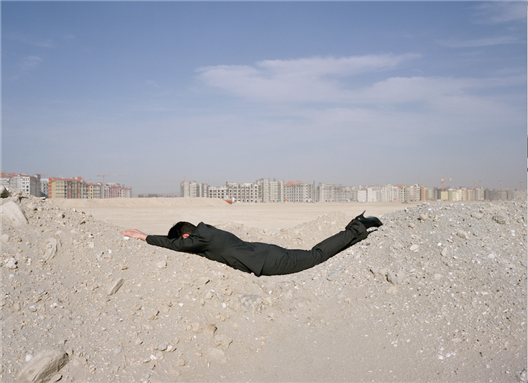

A themed lecture series and discussion forum accompanying each Art Dubai, the Global Art Forum (GAF) is characteristic of the intellectual programming featured by many of today’s largest fairs. The 2014 Forum attested to a concern with history among regional artists, scholars, and curators—a concern perhaps related to the desire to debunk narratives of the spontaneous emergence of Emirati cities and culture from oil-rich sands. Entitled “Meanwhile…History,” GAF 2014 prompted invitees to revise historical narratives by focusing on foundational turning points generally left out of conventional accounts. This historicizing impulse was evident in less reflective form in Modern 2014 as well. Galleries participating in Modern 2014 submitted proposals to jurists for a one or two-artist exhibition, making the case for how each artist has “proven highly influential during the twentieth century and on later generations of artists.”[ii] These selections were further substantiated in an education guide that detailed the biographies and historical importance of each artist, and lent added gravitas by galleries that strove for a classic, mid-century feel, distinguished by their tawny carpeting from the white-cube aesthetic of the contemporary galleries, with their polished concrete floors.

Debates over the conditions of cultural modernization have fueled questions about the constitution of artistic modernism in postcolonial regions. Crucial concerns have included the role of nationalism and the state in supporting modern art as well as that of colonial education and proximity to European modernism in determining aesthetic styles, and how to approach modernisms that strategically revived aspects of traditional styles. Undergirding these issues is the historiographic predicament of how to assert the originality of postcolonial modernisms without the effects of the colonizer’s language, colonial education, and aesthetic influence—or the hegemony of western art historical discourse—leading to their relegation as imitative, derivative, and secondary. One means scholars and curators use to address these problems is what art historian Prita Meier calls “the canon as strategy,” or assembling a roster of “great artists” and arguing for their parity with the canonized geniuses of western art as a means of “legitimate[ing] movements outside the West as worthy of study.” Meier argues that by foregrounding individual artistic genius as the catalyst for innovative development, those who adopt this strategy tend to ignore the influence of social and historical factors.[iii] Indeed, Modern 2014 presented a canon-like assembly of internationally renowned artists such as Sadequain, M.F. Husain, Michel Basbous, and Rasheed Araeen. These artists’ aesthetic achievements were described in short, linear, artist-centric narratives in the accompanying education guide—narratives that largely sidestepped complicated questions of migration, class, political flux, and repression.

[Adam Henein at Art Dubai Modern 2014, Madinat Jumeirah 2014, Courtesy Karim Francis Gallery, Cairo.]

With Modern, Art Dubai appeared to enter the discourse on modernism in the Middle East and South Asia. The fair enlisted a jury of respected scholars and curators, aligning Modern 2014 with publically oriented and pedagogical discourse. Yet it did so with distinctly commercial aims; Modern attempted to lend greater validation to the contemporary art on view elsewhere at the fair by providing historical depth, yet yielded only palatable, individualizing narratives at the expense of a deeper engagement with history. While it may seem easy to dismiss these histories as mere market contrivances, such neat delineations overlook the difficulties of disentangling marketplace, museums, and the academy in a globalized art world in which art histories are being written alongside a powerfully determinative commercial sphere. It is likely that Modern 2014 attracted not only private collectors, but also the many institutional collectors who patronize the fair—collectors working for museums looking to expand their collections of modern art from the foregrounded regions.

If Modern 2014 offers one strategy for consolidating regional art histories, then the fair’s Marker section, introduced in 2011, employs another. Whereas with Modern, Art Dubai cultivates its position as a forerunner of art from the Middle East and South Asia, with Marker it promotes itself as a conduit to emerging markets around the world. Marker 2014 presented contemporary galleries from Central Asia and the Caucuses curated by the artist collective Slavs and Tatars. Like the Modern section, Marker too had an education guide. However, whereas Modern’s focused on artists’ biographies at the expense of more complex questions of site, the guide for Marker focused explicitly on geographical context: alongside artist narratives were profiles of countries where presenting galleries were located, including a sidebar from the CIA World Factbook listing national statistics pertaining to population, industry, arts funding, education, and infrastructure. An officially non-commercial segment of the fair, Marker 2014 was distinguished from the cool white of the commercial galleries with inviting cushioned benches, bright green walls, and a samovar dispensing hot tea. Press material explained that the set-up strove to emulate a chaikhaneh, or Eurasian tea salon. Yet despite the cozy feel, the logic behind Marker’s alleged non-commercial status was hardly opaque; the program serves as an incubator for art from regions that have yet to cultivate a strong international buyer base—locales such as Indonesia and West Africa, to which the two preceding Markers were devoted. In addition to the section’s booths and educational guide, Terrace Talks, a series of discussions exclusively for VIPs, included two presentations on private patronage in emerging markets geared toward increasing “collector and institutional attention to art from the region.”

[Art Dubai 2014 Patron’s Preview, Madinat Jumeirah 2014, Art Dubai 2014.]

In contemporary art as in the market more generally, capital has a tendency to flow into “high-growth” economies, a neoliberal inversion of the less encouraging “underdeveloped.” Yet emerging markets also present barriers to entry in the form of inadequate cultural and linguistic knowledge, as well as susceptibility to volatility generated by economic flux and geopolitical strife. Emerging markets thus require strategic campaigns in order to persuade foreign investors of their viability. However, these campaigns also seek to demonstrate the novelty of their product in order to capitalize on difference. Though Marker adopts the language of “discovery,” Art Dubai also tempers this exoticism with its sensitivity to the art world’s rhetoric of cross-cultural exchange. Yet for all its tastefulness, by strategically packaging these locales for an international audience the fair also enables a more unabashedly speculative approach, whereby art is treated as a financial investment and is subject to cycles of hype generated by dealers and auction houses. For example, immediately following Art Dubai 2014, an exhibition entitled “At the Crossroads 2: Art from Istanbul to Kabul” opened at Sotheby’s London claiming to bring “new content into this much discussed hot new territory,” which included the Caucasus and Central Asia.

While Art Dubai may constitute an art market hub steadily emerging far from the former metropoles of the west, one focused largely on regional art and on cultivating regional collectors, Marker nonetheless suggests that, for all its plurality, the globalization of the visual arts as mediated by the market is not free from neocolonialist dynamics. Rather than revealing a void of cultural context surrounding the global art object, as fantasies of globalized deterritorialization would claim, Marker suggests that the unequal distribution of resources, infrastructure, and authority grants some the power to contextualize the art of geographic Others. Indeed, the expansion of the art market into new regions is usually marked by the appearance of European and US auction houses such as Christie’s and Sotheby’s. Despite the proliferation of the contemporary art market, New York and London remain essential stations of market valorization, together accounting for over sixty percent of imports and exports in the global cross-border exchange of art.[iv]

While Art Dubai exemplifies the manner in which the art fair engages history and place as it assumes greater institutional breadth and gravity, many museums of modern and contemporary art have moved away from both territorial and historical classifications, a curatorial shift tied to the museum’s own increasing evanescence. Museums are opting increasingly for experiential, immersive programming, culturally fluid gallery organization, and changeable collections over more conventional exhibitions, which are marked by chronological, geographical layouts and large, static holdings. These shifts in collecting are evident in museum participation in primary markets for modern and contemporary art (as opposed to secondary markets for more established art and antiquities) as driven by a desire to steer museum holdings in new directions, and in an escalation in the controversial and highly regulated museum practice of deaccessioning works of art, or permanently removing objects from collections.

Though most of its collection has not yet been publically announced, there are indications that the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi will exemplify the trend toward greater institutional fluidity both in its collecting and installation practices. In conversation, Senior Project Manager Verena Formanek expressed disdain for the antiquated nature of the permanent collection, arguing that such a model does not fit the cultural demands of today. What has been revealed suggests that the museum will deemphasize history and locality for the sake of a collection organized by transcultural and transhistorical themes. According to its curatorial charter, the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi aims to “move beyond a definition of global art premised on geography,” foregrounding generic categories such as “Popular Culture and the Mediated Image,” “System, Process, Concept,” and “History, Memory, Narrative.” While the increasingly popular approach of using transhistorical, transgeographic themes to bridge the art of disparate cultures can be culturally progressive, degrading Orientalizing binaries of “East” and “West,” center and periphery, in practice this strategy can run the risk of a dehistoricized aesthetic formalism which can end up only reinscribing hegemonic categories.[v] A greater danger is in producing categories so general and without substance that history itself is conveniently anesthetized. For example, Seeing Through Light—an exhibition of work partly from the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi’s permanent collection that opened in November 2014 in a temporary exhibition space on Saadiyat Island—cohered an international array of artists from the permanent collection around the theme of “light as a primary aesthetic principle in art.”

The Guggenheim may represent the extreme of museum neoliberalization, yet its strategies reflect those being adopted by many longstanding European and US institutions as a means of meeting the pressures of a profit-oriented, global, media-saturated world. As the outcroppings of the Louvre, the British Museum, and the Guggenheim soon to open on Abu Dhabi’s Sadiyaat Island attest, museums are transforming themselves into global franchises in which the cultivation of brand through flashy, starchitect-designed buildings often supersedes other considerations.

[Seeing Through Light: Selections for the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi Collection, Manarat Al Saadiyat Cultural District, Abu Dhabi, November 5, 2014–March 26, 2015, Photo: Erik and Petra Hesmerg, courtesy: Abu Dhabi Tourism & Cultural Authority.]

While the architecture of the global museum is often irrelevant to increasingly changeable museum content, the architecture of the art fair, with its differing microlandscapes, is integral to the fair’s dynamism. The manner in which Art Dubai coheres a heterogeneous array of actors and rhetorics suggests not only its cooperation with different kinds of institutions, nor its simple posturing as civic site, but the coordination of both the permanent and the ephemeral, the civic and the commercial, architectures of the visual arts under a new global paradigm that conjoins fast and slow, global and local, temporalities of cultural production. In this convergence and in Art Dubai’s relationship to the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi we can perhaps see what sociologist Saskia Sassen might call a tipping point: not the wane of an old order and the ascendance of a new one, but a crucial moment in which the capabilities of institutions switch between one relational system or organizing logic and another.[vi]

[i] My discussion of art fairs in this article is not based on any comprehensive quantitative assessment. It is an impressionistic description based on my research and experiences.

[ii] Art Dubai Modern, http://artdubai.ae/modern, accessed 6 Jan 2016

[iii] Prita Meier, “Authenticity and its Modernist Discontents: The Colonial Encounter And African and Middle Eastern Art History”, The Arab Studies Journal 18, no. 4 (2010): 12-45, 30.

[iv] TEFAF. The International Art Market in 2011: Observations on the Art Trade Over 25 Years. Accessed 11 May 2015. https://www.tefaf.com/media/tefafmedia/TEFAF%20AMR%202012%20DEF_LR.pdf.

[v] For some discussion of this, see the Third Text issue on the 1989 show Magiciens de la terre, or Okwui Enwezor’s critique of the first Tate Modern installation in Antinomies of Art and Culture: Modernity, Postmodernity, Contemporaneity (Duke University Press, 2008)

[vi] Saskia Sassen, Territory, Authority, Rights (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006).

![[Art Dubai, Madinat Jumeirah 2015, courtesy: The Studio, Dubai.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/ScreenShot2016-01-20at2.54.31PM.png)